Ready to be stomached

|

Your stomach begins to churn and knead the food you eat.

|

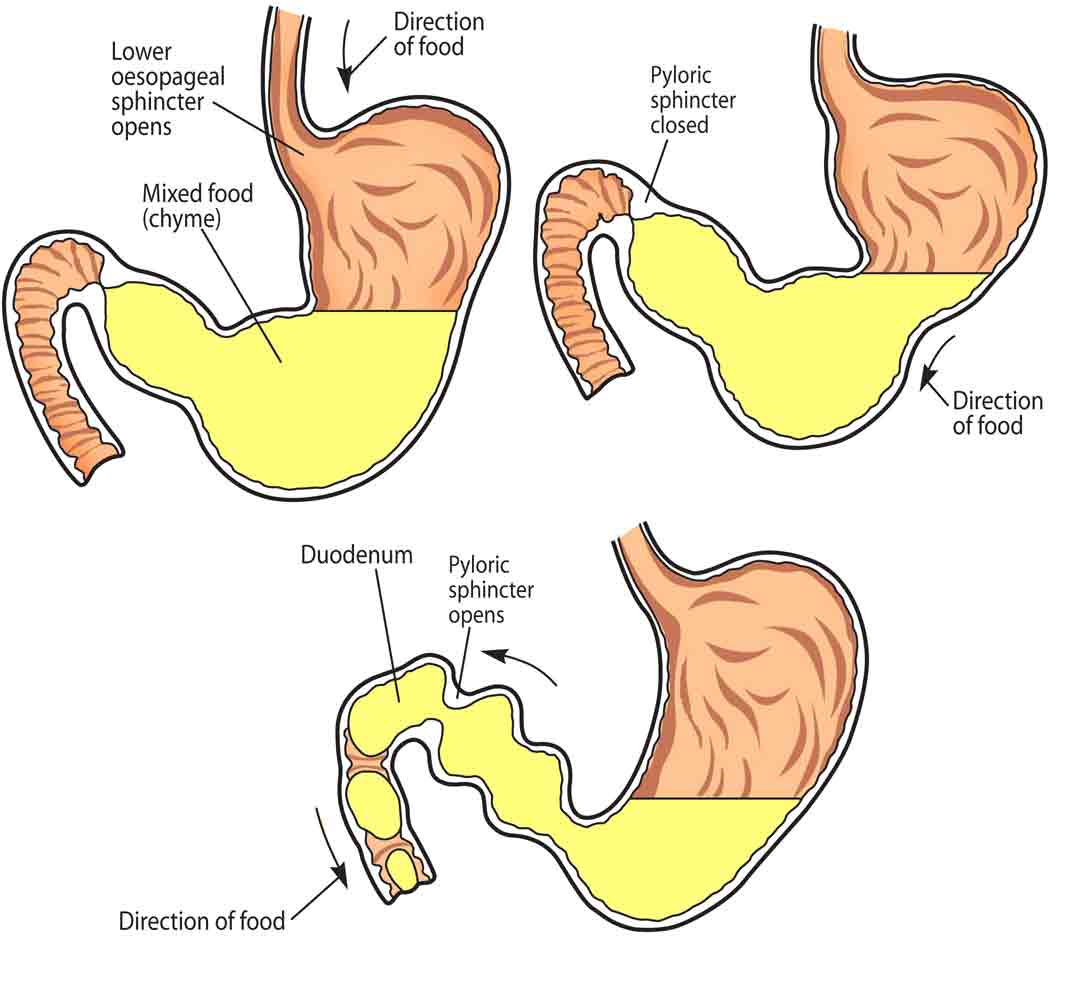

Our chewed cheeseburger has just entered the stomach and is now ready to be digested further. Being the organ which performs various tasks in order to ensure proper digestion, this is the reason why people immediately associate digestion with the stomach. Similar to digestion in the mouth, digesting food in the stomach is also composed of mechanical and chemical processes, which begins the moment food exits the esophagus and enters the stomach. Simple explanation: After chewing and mixing food with saliva and preparing it for further digestion by the stomach, it travels down your throat and esophagus. It then enters your stomach where it is temporarily stored in one of the chambers called cardia. The cardia region of the stomach is directly connected to the esophagus. The entrance to it, however, has a muscle that is always closed except when food is passing through. This keeps the food and fluids inside the stomach, especially helpful when moving around. If the cardia did not have this “lid,” then digestive juices and food particles from the stomach can easily leak out when lying down, bending over, or jumping up and down.

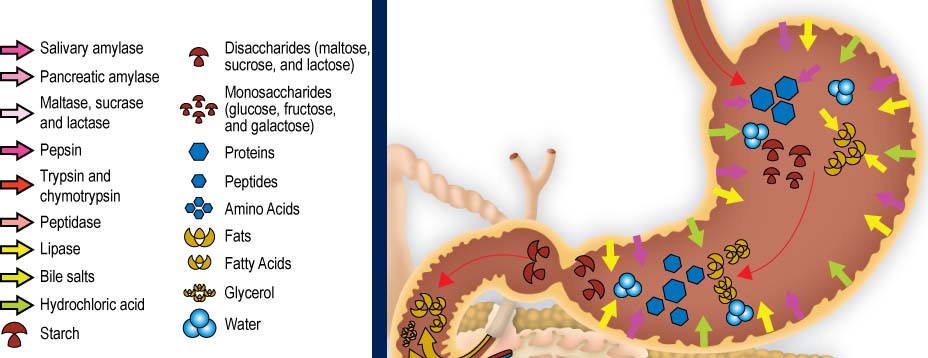

From the cardia, the bolus is pushed towards the center portion of the stomach, where digestive juices, known as gastric enzymes, chemically digest the food by further converting complex substances like proteins and fats into simple components. The stomach also frequently contracts and expands, similar to the chewing motion in the mouth, which mixes the food particles with the stomach juices. This turns the bolus into chyme, a semi-fluid of partially digested food. Most of the complex components of the food that was eaten are broken down as it turns into chyme. From here, it is ready to be gradually pushed towards the intestines where further digestion and absorption will take place. Advanced explanation: The stomach is composed of four regions. The first region is the cardia, directly connected to the esophagus and is responsible for regulating the entrance food to the stomach and preventing the exit of food back up the esophagus. It contains a sphincter muscle, which closes off the passageway between the esophagus and the stomach and only opens to allow food to pass through. From the cardia, food is passed on to the body of the stomach, which serves as storage and as a further digesting mechanism. As the stomach contracts and expands, the bolus is kneaded with the gastric enzymes such as pepsin, rennin, and hydrochloric acid to further breakdown complex proteins and fats. This process also allows the gastric juices to kill most of the harmful bacteria that may be found in the food that was eaten. During this kneading process, gases are produced by the conversion of bolus into chyme. That is why there is a region in the stomach known as the fundus, which serves as a gas bubble. Once there is enough gas in the fundus, it releases it up into the esophagus which would then come out through the mouth or nose. The process is commonly referred to as burping or belching.

Once the chyme is ready for further digestion, it exits the stomach through the pylorus. Similar to the cardia, it also contains a sphincter muscle which keeps the food inside the stomach and prevents chyme from reentering the stomach through it. The pylorus is connected directly to the small intestine, and it regulates the exit of the food at a rate which the small intestine can digest it further. The muscles in the pylorus and the small intestine move the food through peristaltic movements, similar to the movements in the esophagus. Digestion of food in the stomach before it is pushed into the small intestine may take from two to five hours. With this, we leave the stomach and enter the intestine. Or go back to the previous page. |

|